Theoretical Necromancy to Improve Particular Theories

Generative text can serve as theoretical necromancers

A problem with the social sciences is that many researchers often find ourselves reinventing the wheel. As scientists, despite all of our creativity, a situation we commonly share is coming up with a novel idea or theory we think is going to lead some valuable insight, only to find someone else scooped us 50 years ago.

In some sense, it feels as if there is nothing new under the sun. When reading authors like Darwin, William James, Weber, Hayek, and many, many untold others, you tend to get the sense that everything that has to be said or will be said has already been said. In my own work, tracking lineages of thought can be a rather disrupting enterprise - finding, for example, that two models seem similar and produce the same dynamics and only do so because they share the same lineage with one another requires one to go back to the drawing board when drawing implications for something like universal dynamics.

A good thing is that we sometimes catch these things. Historians of science make careers out of catching these things. But often we don’t. And, unfortunately for the careers of historians of science (whom I very much look up to), most scientists don’t read historians of science. So we keep reinventing the wheel.

Is reinventing the wheel such a bad thing? I suppose it means that scientists are thinking about things. It also means that perhaps these things which are periodically resurrected have some sort of value - if someone thought it worked before on this problem and it works now on this problem, then great. But really, reinventing the wheel itself is not a problem, it’s a symptom of a larger issue - that science has little to no memory. There are vast bodies of work, entire literatures, scientific names which once won career medals at their respective societies which have been relegated to historical anonymity.

This is bad because the process can slow science and hinder progress. Imagine you’re trying to get out of a maze. Ultimately, you need to go left somewhere, but every time you backtrack, you forget where you already went right and you continue, once again, down now unfamiliar paths. In a sense, it’s not so bad to re-explore ideas, either - perhaps novelty is overrated; but when revisiting an idea that was previously explored by our scientific grandparents, a familiarity with what was already said provides us with the ability to dig a little bit deeper than they did using our modern tools and epistemic networks. Our lack of memory and rehashing of the same principles also means that for many of our built up beliefs, we cannot draw upon a proper understanding of our foundations.

As far as I can tell, there are a couple of ways in which to improve our theoretical memory.

The first option I can see is to build more robust and resilient theories. One of the reasons why theories disappear from science’s collective purview is that they tend to be particular, or bespoke for a specific purpose. For instance: if I come up with a theory that certain political revolutions seem to be kicked off or catalyzed when a regime banishes or places sumptuary taxes on the peoples’ frivolties, it doesn’t appear obvious that the core components of this theory will show up anywhere else. What does this theory or its individual components tell me about human nature? Are there deeper principles which we can appeal to?

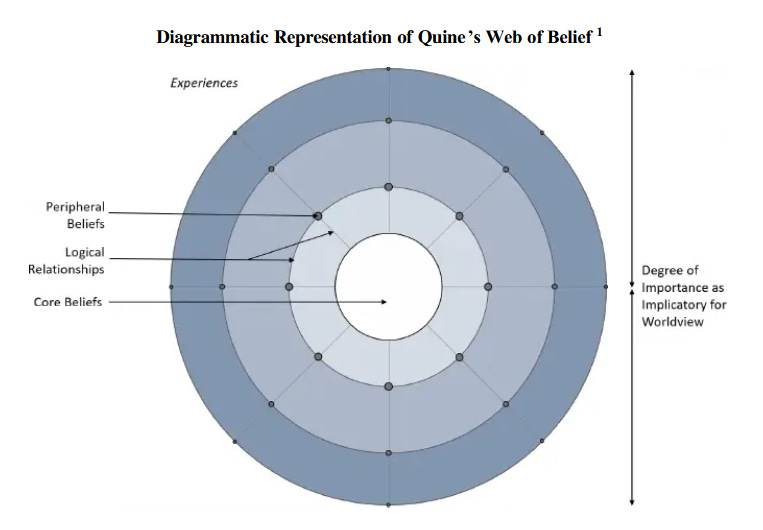

As an analogy for modeling, I’ve started to think about the particular components of theories, the logical presuppositions leading to these components being true or false, and the relationship between theories themselves as constituting a sort of network where these components are the nodes and the employment of them in separate theories or frameworks as the edges. This is not unlike a Quinean Web of Belief (see below). If you think about the structure of this sort of network, a few dynamics might play out here.

One of the things is that concepts which rear their head time and time again in different parts of the system will tend to stick around, while those bespoke theories which are generally non-multipurpose will disappear. My advisor published a paper several years ago showing that nodes which have multiple connections with one another tend to exhibit more resiliency in the face of information loss - what him and his co-authors call structural entrenchment. In our world of idealized theories, this means that concepts which continue to show up will tend to be the most resilient. The job of the scientist then is to develop more resilient theories by appealing to more general, rather than bespoke, principles. Through this, progress is scaffolded, as we don’t have to continuously reinvent the wheel.

Now, this is what we are supposed to be doing. By finding general principles, we are able to cover a lot of ground when we are faced with new problems, and the fact that these principles transfer across many problems reads to me that the principles are likely true. But one problem I see with this is that sometimes the bespoke is simply true - perhaps it is the case that people revolt when their cigarettes are taxed. We can come up with a very nice threshold model which says something about tipping points and when people get angry, but in the process, we lose a property of the emergent system that is worth attending to: if you want to predict when a revolution will happen, perhaps the heuristic provided by looking for modern day equivalents like the Tea Act are enough for the type of people working on revolution. They don’t need to build an Ising model (although for fun they should).

Our theoretical ecology here then gets messy. Bespoke phenomenological theories of these emergent behaviors are where we start losing information and forgetting things. It’s how we got to where we are today, and I have unfortunately informed you that today’s theoretical ecology is not ideal. But I do see a way out.

Our second option is to find the human-limited processes of scientific and theoretical discovery and augment them in some way, with something, that can overcome our shortcomings. We are, afterall, limited beings. I think despite what others have said, we don’t necessarily come pre-equipped for science. Rational discovery and learning, yes, but not the collective behavior we call science. In other words, what if we could read all the literature relevant to our current topic. What if we didn’t forget things. A lot has been said about the philosophy of science in these regards, but what if humans weren’t at the wheel?

After exploring ChatGPT and GPT-3 over the last several weeks, one of the things which strikes me is its ability to summarize obscure and poorly-written information in a manner in which humans can understand it. A lot of people have lamented on the death of the college essay due to these, in my opinion, rather stupid models. I am less struck by its (in)ability to synthesize information in a consistent manner and am more struck by its ability to pull relational concepts out of the grave. I can ask ChatGPT about Durkheimean suicide and who else has worked on the topic - it will tell me places to look. With its own limited and generalist training, I can provide it with a theory and ask who else has asked about it. More than anything, these things function as the idealized search engines of our dreams - apt comparisons between Google’s non-functional search system and ChatGPT’s ability to tell you exactly what you want to know are readily abound on the internet right now.

If trained on the right information, generative text models can serve as our theoretical necromancers. Their search goes deeper and wider than our search. It doesn’t have to synthesize information the way we do. All it has to do is find relational similarities and tell me who else has thought about this before - like Christ descending into hell to save Adam, the search provided by these chat models can resurrect our dead and lost theories.

This idea is somewhat similar to the idea of using recommendation algorithms to find novel zones of discovery in science, but I think theoretical necromancers, instead of shining a flashlight onto new avenues of exploration, can serve as a way of trimming down our epistemic network. Similar to the neural pruning that takes place during childhood development, what these tools can provide us with is a way of trimming spurious nodes and links, streamlining our epistemic networks, and giving us a primitive Hobo Code, telling us others have been here - be sure to have new stuff if you want to continue, or at least be aware you’re stamp collecting (a term I don’t intend to use derogatively, stamp collecting means reinforcing ties).

Reworking our particularist theories with Option 2 doesn’t make Option 1 (making better general theories) obsolete: it makes Option 1 more likely. As we begin to prune useless ideas and spurious exploration by looking to see where we’ve already been, and we can better see the shape of the maze we’re in - after some time, as we start to see our particular things look like the particular other things others have worked on, we’ll find exploration of the particular drives us closer towards the general. At least I hope.

My proposal then would be something like this: I have a use case for GPT and ChatGPT. A lot of people are either looking at these systems as horrible for the future of creative work (of which both science and writing school essays are a part of) or as usless and cute toys we’re going to forget about in several months’ time. I see a rather obvious and powerful tool for overcoming our limited collective memory.

We should build these for particular fields to increase their theories: SociologyGPT might do a lot of work, or better yet, PsychGPT might be the most necessary right now. After these are built, we can link them up - find consilience, and bolster our global epistemic networks. If I weren’t a PhD student and had infinite resources at my disposal, this is something I’d want to work on.