Translation: Joseph Ratzinger and FA Hayek in Conversation

From the Salzburger Humanismusgespräche, 1976

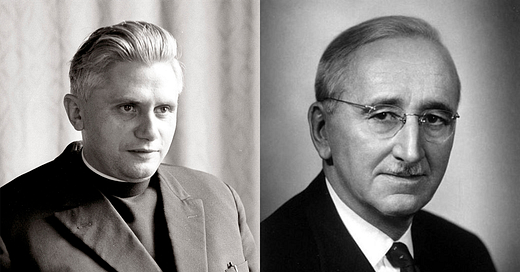

I came across an article last year describing a panel held in 1976 on the Role and Self-Image of Intellectuals. Part of a longer series on general humanist topics, the panel included a number of discussants, mostly from journalism backgrounds, but also significantly included 49-year-old, then theology professor, Joseph Ratzinger and 77-year-old Nobel laureate Friedrich Hayek. Hayek’s comments, unsurprisingly, argue that the role of intellectuals in public life are overblown, and he is more or less dismissed by the other panelists, save for Ratzinger, who speaks last.

Wanting to read more on it, I’ve translated the recording of the panel from its original German and will host it here, as I have done with previously with an older Hayek lecture, on Evolution and Spontaneous Order:

Announcer:

“The Role and Self-Image of Intellectuals Today” is the topic of our night studio broadcast today in the Farewell to Utopia series. With contributions from the 8th Salzburg Humanism Talk of the ORF. Introductory words and the structure by Dr. Oskar Schatz.

Oskar Schatz:

That the role and self-image of intellectuals today not only diverge widely, but are often in contradiction, was an assertion heard very often at this eighth Salzburg Humanism Seminar. Helmut Schelsky, for example, was of the opinion that the belief of intellectuals in their continued informative role was nothing more than self-deception and illusion, which they had to hold on to in order not to fall into the abyss of their profession, which they had hidden from themselves. In reality, the contribution of the intellectual producers of meaning consists above all in the uncertainty of the people who are directly active in practice, but above the common man, whom they alienate from the last remnants of their own experience through their quixotic abstractions.

But the Freiburg political scientist Wilhelm Hennis also sees the predominance of the principle of hope, this favorite idea of the progressive, utopia-believing intelligentsia, as a destruction of the caring, given-minded thinking that decisively determined politics until the beginning of modern times; and subsequently through the futuristic, constructivist and rationalist thinking of utopia, has been replaced. The Eros of theoretical knowledge corresponds to a unique belief in practical knowledge, a world orientation that enables rational action, but which is becoming increasingly difficult due to the lack of common basic beliefs and moral religious standards. When theoretical knowledge weighs down one side of the scale, the other side seems to have been wiped clean. According to Hennis, clarifying this connection is the most important task of intellectuals today: Utopian Rationalistic or caring thinking that turns to the factual. The demands and mission of intellectuals today could very well be measured against these options.

Listen to excerpts from a discussion led by Professor Ulrich Hommes Regensburg, in which the economist and Nobel Prize winner Friedrich Hayek, the Berlin political scientist and cultural critic Richard Löwenthal, the editor of the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Robert Leicht and the Catholic theologian Joseph Ratzinger have their say. The discussion begins with Professor Friedrich Hayek's verdict.

FA Hayek:

In the house of the hanged man you don't talk about ropes, just as you shouldn't talk about intellectuals in a radio studio. But they are an unmistakable force, even if we are not entirely clear who they actually are. About 25 years ago I tried to define them in English as the “second hand dealers in ideas”, i.e. junk dealers of ideas. And I've found over time that this really highlights a class that sets them apart from other people who are sometimes included among intellectuals.

There are, in my view, three important groups here: there are intelligent people; there are professionals, which very often include very important scholars; and thirdly, there are intellectuals. These are three completely different groups. The intellectuals are people who have mastered the technology of imparting knowledge, but who basically understand nothing, or at least have no knowledge of a subject at all, and who nevertheless owe their prestige not to intellectual achievements, but to the effort to persuade the world to accept the ideas that they have picked up somewhere else. They obviously have a tremendous influence in today's world. One of the speakers made the comment that the intellectuals are unavoidable - I don't know what expression he used - he did not exactly say harmful, but I think although [intellectuals] are unavoidable, they are harmful. It is, in the narrow sense, as I use the word now, a very serious problem.

Because although the intellectuals, as I define them, as “second-hand dealers in ideas”, don't really understand anything, but rather want to make effective ideas that they have come across and whose dissemination is their business, today's world and public opinion is dominated by these professional mediators of ideas. It has become so threatening because it is where unheard-of ambitions arise about what people can arbitrarily do with society. In general, it was not experts who created utopias. The utopias in the sense in which they have been discussed today come from intellectuals in my narrow sense. People who are not experts, people who I would almost say do not belong to my first group of intelligent people, but who belong to the group of professional mediators of ideas. And it is due to the drive of the professional mediators of ideas that there is a constant effort to do everything. The ugly word feasibility has, with some justification, gained popularity recently. The idea that everything is possible is, of course, the modern form of utopia, which is currently being pursued by intellectuals and which is the unheard of field of activity in the special form of democracy that we have today.

A democracy is characterized by the fact that it is a fundamentally unrestricted form of government and that is terribly weak precisely because it is constantly having to buy support from interest groups. Because it is able to satisfy interest groups through special measures, it must do so. So we have an all-powerful tool, an unrestricted democracy, which is promoted by the fact that socialism needs it for its purposes. One could not strive for socialism without unlimited power, which, once it exists, as long as it is run democratically, is exploited by interest groups that can harness intellectuals to claim that they have a special merit or a special claim.

That is the situation we live in today. It worries me terribly because democracy, which in its elementary forms is the only protection of our personal freedom, is actually becoming so discredited that more and more serious people, whom I respect extremely, are becoming extremely skeptical about democracy. This leads to the problem, which seems to me to be the central problem of today, that democracy can only be maintained if we combine it with limited government power. But the prevailing theories believe that democracy, by definition, must retain unlimited government power. All my efforts over the last few years have been directed towards drawing up a plan under which it is possible, indeed, not to assign any other power to the democratic representative authorities, but still to limit their power. If we do not succeed in doing this in some form, I am convinced that democracy will destroy itself. Thank you very much.

Oskar Schatz:

Ladies and gentlemen. I think it was in all of our interests to let Mr. Hayek really speak so fully. It was a moving verdict and thank you from all of us for it. I would like to suggest that we keep the discussion brief and simply take advantage of the opportunity to exchange ideas more often. I would like to ask, Mr. Löwenthal, that you might be the next to speak, because you yourself have dealt with the cultural crisis here and have seen a very specific positive meaning in the function of the intellectuals.

Richard Löwenthal:

Yes, I don't want to address Mr. von Hayek's remark now, except to say that I have absolutely nothing to do with his definition of intellectuals, except that it is very silly. I believe that among the intellectuals to whom I count myself and to whom I also count Mr. von Hayek, despite his protests, there are many important thinkers. I believe that there are important, original thinkers among the authors of utopias, even of destructive utopias, and that it is not so easy for intellectuals to define a category that they consider to be parasitic. But that's not what I signed up for.

My great experience is that I have seen the mechanism of the cultural crisis in a relationship in a one-sided way. I thought too much of the left-wing intellectuals as the bearers of the cultural crisis, out of desperation for our society, despair of our values. I overlooked the extent to which there are also conservative romantics who are responsible for our cultural crisis. And that was thoroughly demonstrated to me. I think I would first like to illustrate the definition of utopia by my friend Wilhelm Hennis. Mr. Hennis referred to Ernst Bloch's principle of hope, and Ernst Bloch is of course one of our great utopians. But it doesn't follow from this that everyone who operates with hope is a utopian. That's not the same thing. The principle of hope in Bloch's sense and hope in social matters in general. And in any case I would consider it extremely questionable if we wanted to replace the principle of hope with the principle of resignation in social matters. It is true that you cannot improve at will and that in reality it is often just a matter of being able to preserve something. But you can only preserve things in a dynamically changing world by improving. This is a false antithesis. And it seems to me that what most people call reform, including, by the way, what constructive conservatives call reform, is precisely a change for the purpose of preserving the fundamental content of our culture and our fundamental values.

Now a word about Mr. Schelsky's intellectual definition. It seems to me that it is of course possible to choose a definition of an institutional nature. Definitions are free if you stick to them. It is of course possible to say that I define intellectuals as those who work as mediators of meaning in the areas of teaching, in schools and universities, in communication, in the media, in social care and in theology, etc. But it seems to me that what Schelsky said about these institutions and their members does not agree with this definition. First of all, it is not true that these institutions as a whole essentially have an oppositional function. The fact is that modern society would be inconceivable without the general non-ideological achievements of schools and universities and that one of the essential features of what Daniel Bell calls the post-industrial society is the enormously increasing productive importance of the teaching apparatus. Of course, this also applies to a considerable extent to the communicative mediation apparatus and also to the social apparatus and the functions of these institutions. Simply equating them with the ideological activities of some of their members seems to me to be doing these institutions an injustice. Furthermore, it is not the case that one can simply call these institutions oppositional institutions, even if they are sometimes used that way.

My experience is that universities in general have not become oppositional institutions, but that some universities that fell into the hands of professional oppositionists have been destroyed as institutions. This is a completely different process than the transformation into opposition institutions. In fact, in the course of his presentation, Mr. Schelsky actually moved from the institutional definition of intellectuals to a different definition, which is not as narrow as that of Mr. Sontheimer, who criticized the bearers of left-wing theory, but which is still too narrow is, insofar as it uses a certain attitude that he rejected and, incidentally, that I rejected in this form, as a definition of the intellectual. It seems to me that there is a task for the intellectuals in the sense of critics, which of course so often and here I build on their initial comments. Everyone defines the intellectuals as they want, and the question is whether they include themselves, which of course is often carried out in such a way that it becomes a fundamental criticism of our system and our values, which in other cases is carried out in such a way that it becomes an effort to improve this system and renew these values. And in still other cases it is carried out in such a way that it is used as a nostalgic defense from positions that are no longer tenable.

Oskar Schatz:

Gentlemen, I would suggest that we do not skip over these two important points with new arguments. But if something else needs to be argued along the same lines, please do so now. Mr. Leicht.

Hubert Leicht:

So the question is, given the whole web of moods and opinions, how much chance do we still have of a discursive dialogue? I can only try to cast a vote with modesty, because I'm always bothered by this mixture of hidden whinyness and aggressiveness that sets the tone wherever they discuss intellectual issues. There is also a mixture of sometimes dismay, serious concern, and then complacency and even insult. And if Mr. Schelsky used the term “show talk”, then I would of course also like to ask him whether he checked every sentence to see whether it was not simply spoken with effect, i.e. with consideration of the effect or that of polemical fun. Well, I don't want to empty my head, but Mr. Schelsky, you don't condense the group of intellectuals with all their admittedly human, erring, evil, poisonous traits, but not just these traits, into a schema that certainly has a certain illustrative realism, but at the expense of a great loss of reality. Where such a rough scheme is created, which is in no way inferior to the elementary or primitive criticism of capitalism.

So that's basically the animism that Mr. Hennis was talking about - it is the process of stylizing a thing to such an extent by increasing abstraction that it can be reduced again all the more effectively. I don't know if I don't accuse you of that, personally. But don't you see the danger of simply gaining false approval from a certain bourgeois mentality? I don't want to assume this to you either, I make it clear again and again, whether you don't get an echo from people who bring a denunciatory tone to what you want to say. Whatever lies in all this personalization and group training is arbitrary or involuntary. I mean, Mr. Sperber made it clear to us that intellectuals are people like other people, no better, no worse. But if you leave the common man and the worker unexplained to a certain extent, i.e. put forward an ideal of purity against the intellectuals, then I have to say, you are in the same romanticism in which anti-capitalism is exalted with its workers. Then a remaining stock of good people is retained. And now what is this common man? Where exactly does this come into play for you? Where do you really have anything in common with him?

You refer to a common man as an ideal and reject the role of the intellectual. That's too oscillating for me. You'll just have to give up your professorship and go into production at Hoesch if you're really serious about it, at least make a guest debut there. So the question is subjective. Isn't an intellectual party and conflict of ideas, in which the individuals are less in line than their opponents assume by hypostatizing them and creating an enemy image, being carried out on the basis of structural problems? And objectively, what Mr. Schelsky presents to us as new, as fundamentally new, is not the draping of the age-old accusation of decomposition against the intellectuals, here exaggerated to eliminate the entire parliamentary interplay between government and opposition, which is actually not new. Although it does, it is own way, I have to admit, sounds original.

Now I'm sorry that I won't be able to see Mr. Hennis shortly. I can only make three points. I was very impressed and worried here. Still, three questions. Ecumenism: is this just a loss? Is this just a danger? I see the danger you describe. But we experience every day that it also brings profits. I don't just mean this in a vulgar economic sense. Question: can we, from this ecumenism, understand ourselves in a completely positive way from this ecumenism, so to speak, to the protected existence of provinciality in this Province Humaine? But can we simply retreat regressively? Don't we have danger and opportunity? It is precisely on the second question that you are really allowed to monopolize the concern only, let's say, on those who preserve it? There you may be a danger. To monopolize something, like the utopians or the left monopolize the good for themselves. And thirdly, and perhaps we will hear more from Mr. Ratzinger, I want civic religion. As much as I like your plea as a human being, I can only imagine that the good Lord will give us a good slap on the wrist for talking like this about what He has in mind for us. At the end of the last days I am not sure whether he will tolerate us functionalizing him in this way as a prerequisite for proper governability.

Oskar Schatz:

Mister Ratzinger, please.

Joseph Ratzinger:

Yes, in view of the quickly-moving time, I would just like to make a very brief comment that was inspired by Hayek's verdict. [He] made it clear to me that we are all fighting more or less in vain against the origin of the word that Mr. Amery has drawn attention to, and that this silent duel with the actually historically shaped content then leads to further ambiguities. So that it seemed right to follow his verdict and to understand the word again in its original historical form. Manifest is intellectual: this means that people express themselves on general human and moral problems and, in doing so, risk the prestige of their intellectual significance elsewhere. If you look at this origin, it seems to me that Mr. Hayek was not as absurd in his definition as it seemed to be in Mr. Löwenthal's verdict; but to a certain extent that in its initial substance was someone, who based on certain reasons has intellectual prestige but then brings this prestige to bear in the general humane, which is not his profession.

Now I would say that if this is actually the original content of the word intellectual, which always comes through and cannot be eliminated, I would like to evaluate it differently than Mr. Hayek did, because he tacitly recommends, just as Mr. Schelsky did in a similar way, that everyone should retreat to their own field and then everything would be right. And I would say that in the end that's exactly what doesn't work. Because if this happens, that everyone withdraws to their professionalism, where they can really speak competently, then it becomes clear that the actually human questions do not appear anywhere: that they cannot be the subject of science and, if that is the case, the intellectuals have to exclude people incomprehensibly, and that they are, so to speak, scientifically forbidden.

Then the question is, where does this have a place? And that is actually the crisis, which is very closely related to the concept of science and the demands of science. And in this situation, Mr. Schelsky offered us the myth of the simple person as refuge and storage for previously rejected basic values, so to speak. So they are present there, and that doesn't seem to be a solution at all to me, but rather a myth. What characterizes the theologian, who is probably not or cannot be an intellectual at all, is that he did not live among intellectuals, but among simple people, and therefore knows that this myth is a myth. I believe, we are trying to get to the point where we respect and preserve the objectivity of science, which cannot accommodate people as human beings precisely because of the way objectivity has been defined, as a valuable asset. But at the same time we feel our way back to a spiritual objectivity that cannot satisfy these criteria, but conversely also refuses to leave everything that lies outside of it to subjectivity. And I would say that this was actually the legitimate attempt of medieval philosophy and theology: to go beyond mere subjectivity and to establish a discipline of reason here. I admit that [theology] has done this shamefully poorly, and to that extent I am happy to accept everything that Mr. Schelsky says about theologians. I believe the effort that it has pushed: namely to establish a discipline of reason even in this area that cannot be objectified, and thereby achieve the communicability of reason and expand reason’s space beyond what can be grasped through science alone, is the [effort] that is urgent today.

Announcer:

In today's broadcast of the night studio series Farewell to Utopia, we heard excerpts from a discussion on the topic of the role and self-image of intellectuals, today with contributions from Friedrich Hayek, Richard Löwenthal, Robert Leicht and Joseph Ratzinger. You can hear the next Salzburg night studio on December 15th. We present excerpts from the presentations by Professor Wilhelm Hennis and Professor Robert Spaemann under the title “Science as Utopia” Beliefs in a Hypothetical Civilization.”